(1) History and Physical Exam

(2) Objective Data

(3) Documents

(4) Pain Treatment

(5) Decision: Maintain, Alter, Taper or Discontinue

The following is derived from an article that appeared in Louisville Medicine (September 2018). This is not an exact reprint. Some Internet links, references, graphics and phrasing have been updated for accuracy and relevancy • James Patrick Murphy MD, April 9, 2019

Providing therapeutic continuity for patients who have abruptly lost access to their prescriber (e.g. pain clinic closure) can be a challenge, especially if the patient has been treated with opioids and other controlled substances.

A patient in pain, facing the possibility of worsening pain combined with medication withdrawal, can feel very stressed. In this potentially difficult scenario, the caregiver must convey an air of calmness and empathy. Providers may seize this clinical inflection point as an opportunity to redirect the course of treatment, or provide a therapeutic bridge to specialty care by way of referral or consultation.

While not meant as a substitute for more comprehensive guidelines, the following is a concise five-step initial approach to caring for the displaced pain patient on chronic opioid therapy.

Always exercise compliance with statutory requirements. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/key-issues/pain-management-by-state.pdf

FIVE STEPS

STEP ONE • History and Physical Exam

- Establish a diagnosis

- Assess for withdrawal symptoms (Ref 1: Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale)

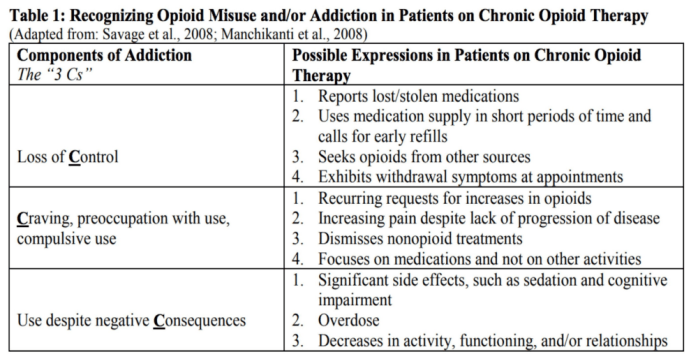

- Note behaviors indicative of drug abuse or diversion (Ref 2: Knowing When to Say When: Transitioning Patients From Opioid Therapy, pg 19)

STEP TWO • Objective Data

- Check state Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (e.g. KASPER) https://operationunite.org/investigations/kasper/

- Count the patient’s current supply of pills

- Review (and/or request) medical records and reports (e.g. MRI)

- Do a urine drug screen https://kbml.ky.gov/hb1/Pages/Considerations-For-Urine-Drug-Screening.aspx

- Screen for:

-

- Function (Ref 3: PEG Scale: Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity)

- Opioid abuse potential (Ref 4: Opioid Risk Tool)

- Mental health (Ref 5: Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-4)

-

- Remain alert Remain alert to signs of anxiety, depression, and opioid use disorder. If signs of opioid use disorder then offer or arrange for treatment. If signs of mental illness then offer or arrange for treatment. https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/

- If child bearing potential, order a pregnancy test.

-

- Immediately consult OB/GYN if pregnancy is confirmed.

- Opioid withdrawal during pregnancy has been associated with spontaneous abortion and premature labor.

-

STEP THREE • Documents (may be combined into one)

- Informed Consent (Ref 6: NIDA Sample Informed Consent)

- Treatment Agreement (Ref 7: NIDA Sample Patient Agreement Forms)

STEP FOUR • Pain Treatment

- Maximize use of nonpharmacologic and nonopioid pharmacologic treatments as appropriate. (Ref 8: Treating Chronic Pain Without Opioids, CDC)

STEP FIVE • Decision: Maintain, Alter, Taper or Discontinue. A decision regarding maintaining, altering, tapering, or discontinuing controlled substances must be made. Some stable patients might be well served by maintaining their current regimen, however you are under no obligation to prescribe or continue with a treatment plan you don’t agree with.

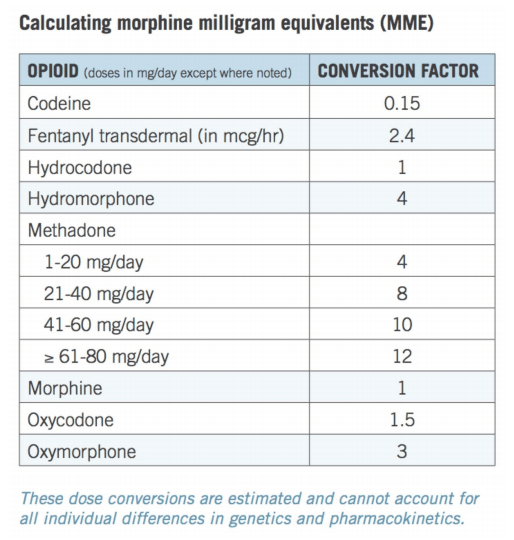

- If the patient does not need a prescription and still has some medication, advise on how to gradually taper (i.e. decrease 10 to 50 percent per week). To prescribe a taper with controlled substances: Calculate the current Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (Ref 10: Calculating Total Daily Dose of Opioids For Safer Dosage, CDC)

-

-

- Initially prescribe zero to three days of a reduced MEDD (e.g. decrease 10 to 50 percent)

- Use immediate release medications

- Arrange follow up early and often

- Additional days of medications may be prescribed at follow up if risk/benefit assessment is deemed acceptable by the prescriber

- The CDC advises against a rapid taper (e.g. three weeks or less) for people taking ≥90 MEDD

- Regardless of taper speed, withdrawal may still happen

-

-

-

-

- Assess for withdrawal symptoms (Ref 1: Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale)

- Advise on over-the-counter medications for withdrawal symptoms (Ref : ASAM National Practice Guideline, Part 3, pg 29)

- Consider prescribing prescription medications for withdrawal (Ref 11: ASAM)

-

-

From ASAM: The Guideline Committee recommends, based on consensus opinion, the inclusion of clonidine as a recommended practice to support opioid withdrawal. Clonidine is not US FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid withdrawal, but it has been extensively used off-label for this purpose. Clonidine may be used orally or transdermally at doses of 0.1–0.3 mg every 6–8 hours, with a maximum dose of 1.2 mg daily to assist in the management of opioid withdrawal symptoms. Its hypotensive effects often limit the amount that can be used. Clonidine can be combined with other non-narcotic medications targeting specific opioid withdrawal symptoms such as benzodiazepines for anxiety, loperamide for diarrhea, acetaminophen or NSAIDs for pain, and ondansetron or other agents for nausea.

-

-

-

- If tapering benzodiazepines, do so gradually.

- Risk mitigation topics e.g. CDC Guideline Factsheet https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/guidelines_at-a-glance-a.pdf

- Discuss with patients undergoing tapering that, because their tolerance to medications may return to normal, they are at increased risk for overdose on abrupt return to previously prescribed higher doses.

- Consider offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose, such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid dosages (≥50 MEDD/day), or concurrent benzodiazepine use, are present (Ref 12: Opioid Reversal With Naloxone, NIDA)

-

-

REFERENCES:

- Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf

- Knowing When to Say When: Transitioning Patients from Opioid Therapy University of Massachusetts Medical School (Massachusetts Consortium) Jeff Baxter, M.D. April 2, 2014 https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/knowing_when_to_say_when_3-31-14_ln_sd_508.pdf

- PEG Scale (Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity) http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/pain/PEG.Scale.12.2016.pdf

- Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ 4) https://www.oregonpainguidance.org/app/content/uploads/2016/05/PHQ-4.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Sample Informed Consent Form https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/SampleInformedConsentForm.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Sample Patient Agreement Forms https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/SamplePatientAgreementForms.pdf

- CDC: Treating Chronic Pain Without Opioids https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/training/nonopioid/508c/index.html

- CDC: Opioid Factsheet for Patients https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/AHA-Patient-Opioid-Factsheet-a.pdf

- Calculating Total Daily Dose of Opioids For Safer Dosage (CDC) https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf

- American Society of Addiction Medicine National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use, Part 3: Treating Opioid Withdrawal, Summary of Recommendations (7), page 29. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf

- Opioid Reversal With Naloxone (NIDA) https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/opioid-overdose-reversal-naloxone-narcan-evzio

ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED REFERENCES:

- CDC Checklist for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/PDO_Checklist-a.pdf

- Universal Precautions Revisited: Managing the Inherited Pain Patient by Douglas L. Gourlay, MD, MSc, FRCPC, FASAM,* and Howard A. Heit, MD, FACP, FASAM. Published in Pain Medicine Volume 10 • Number S2 • 2009 https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/10/suppl_2/S115/1836861

- SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/

- Federation of State Medical Boards, Pain Management Policies, Board-by-Board Overview http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/key-issues/pain-management-by-state.pdf

- Knowing When to Say When: Transitioning Patients from Opioid Therapy University of Massachusetts Medical School (Massachusetts Consortium) Jeff Baxter, M.D. April 2, 2014 https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/knowing_when_to_say_when_3-31-14_ln_sd_508.pdf

- The Pain Clinic Closure Survival Guide for Patients and Clinicians https://jamespmurphymd.com/2018/08/01/pain-clinic-closure-survival-guide-for-patients-clinicians/

- Patient Education Resources:

- Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure, Education for Patients https://kbml.ky.gov/hb1/Pages/Considerations-For-Patient-Education.aspx

- VA: Patient Education https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Opioid_Safety/Patient_Education.asp

- VA: Taking Opioids Responsibly https://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/policy/Taking_Opioids_Responsibly_2013528.pdf#

- Murphy, James Patrick. 5-Step Initial Approach to Caring for the Displaced Pain Patient on Chronic Opioid Therapy. Louisville Medicine, September 2018 https://s3.amazonaws.com/seak_members/production/12419/original/5-Step_Approach_PDF.pdf?1536724268

Calculating MME, from the CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf

Disclaimer: This is for informational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice or a patient/provider relationship. It is not meant to establish a standard of care. I have made every effort to cite references where applicable, however the opinions expressed are my own and have not been endorsed by any organization. Links to references or other materials are taken at your own risk. The content provided here is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor, go to the emergency department, or call 911 immediately.

James Patrick Murphy, MD, MMM, FASAM is a board-certified Pain Medicine and Addiction Medicine specialist who represents the American Society of Addiction Medicine on the American Medical Association’s newly formed Pain Task Force.