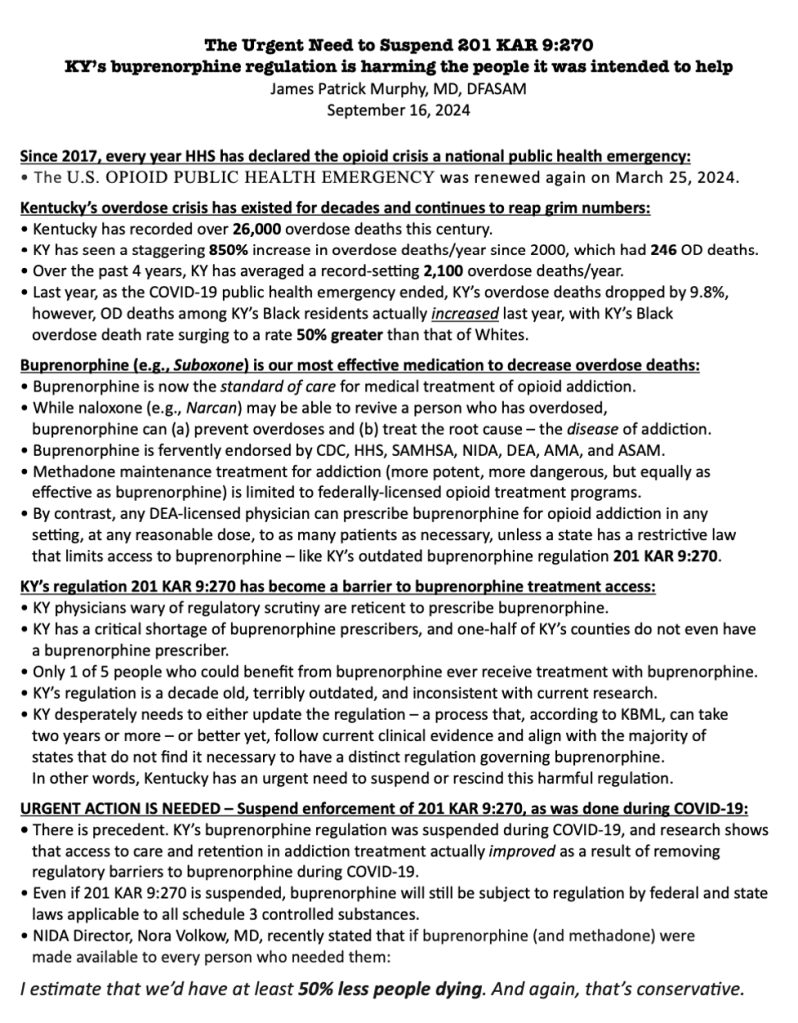

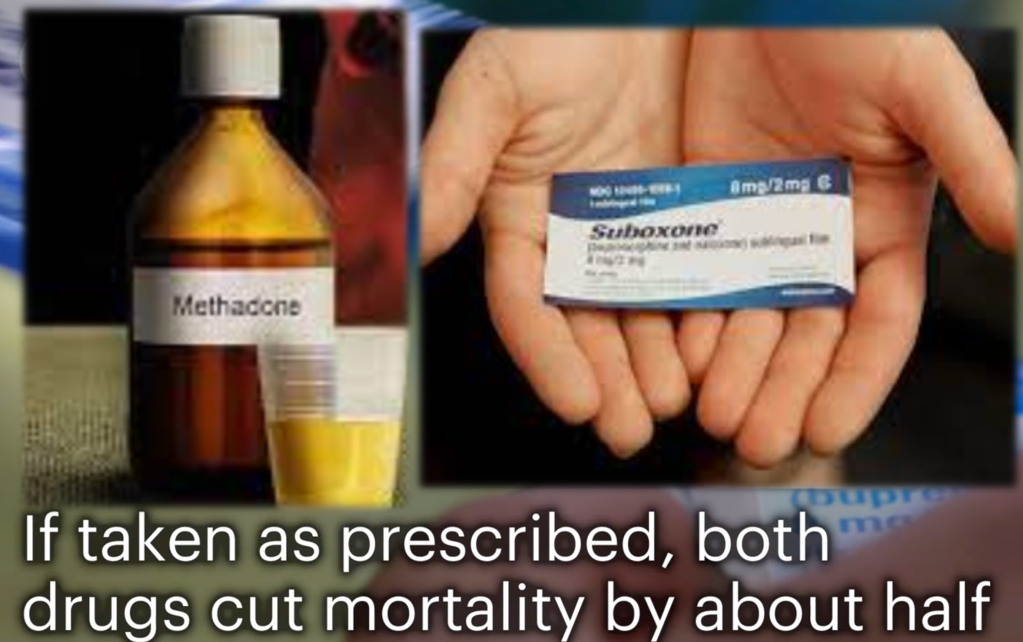

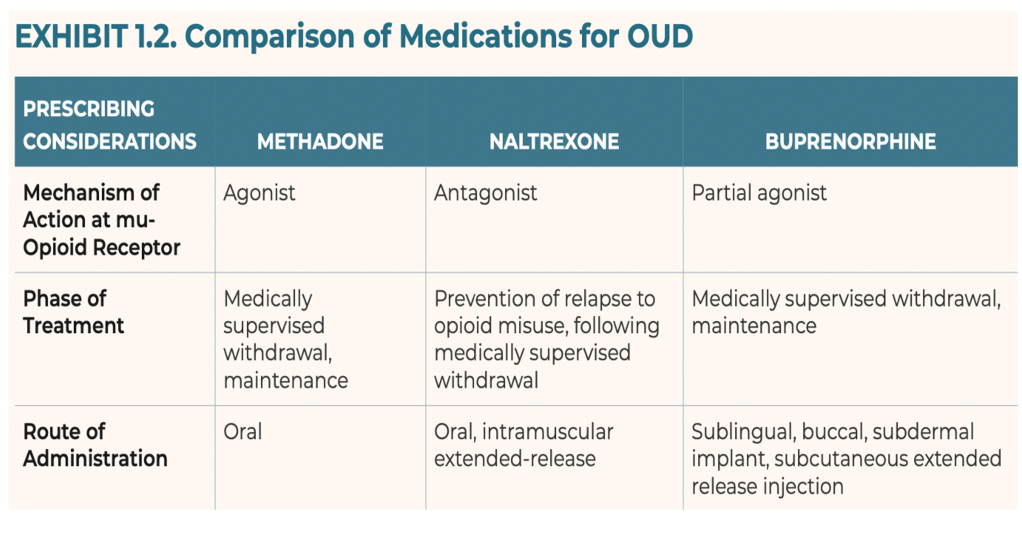

Buprenorphine is an FDA-approved medication for treating opioid use disorder, proven to be effective in preventing overdose deaths, reducing drug related crime, recidivism, and drug diversion, while saving valuable community resources.

However, Kentucky’s buprenorphine prescribing regulation 201 KAR 9:270 is outdated, unnecessary and harmful, because it creates barriers to accessing this lifesaving care.

Furthermore, despite all good intentions, this regulation paradoxically increases crime and diversion. Thus, for the safety of our communities, 201 KAR 9:270 must be repealed.

• Eliminating 201 KAR 9:270 is a simple way to increase access to buprenorphine, fight crime, and save money. More importantly, Kentucky’s overdose death rate could potentially be cut in half if every Kentuckian who needs buprenorphine could get.

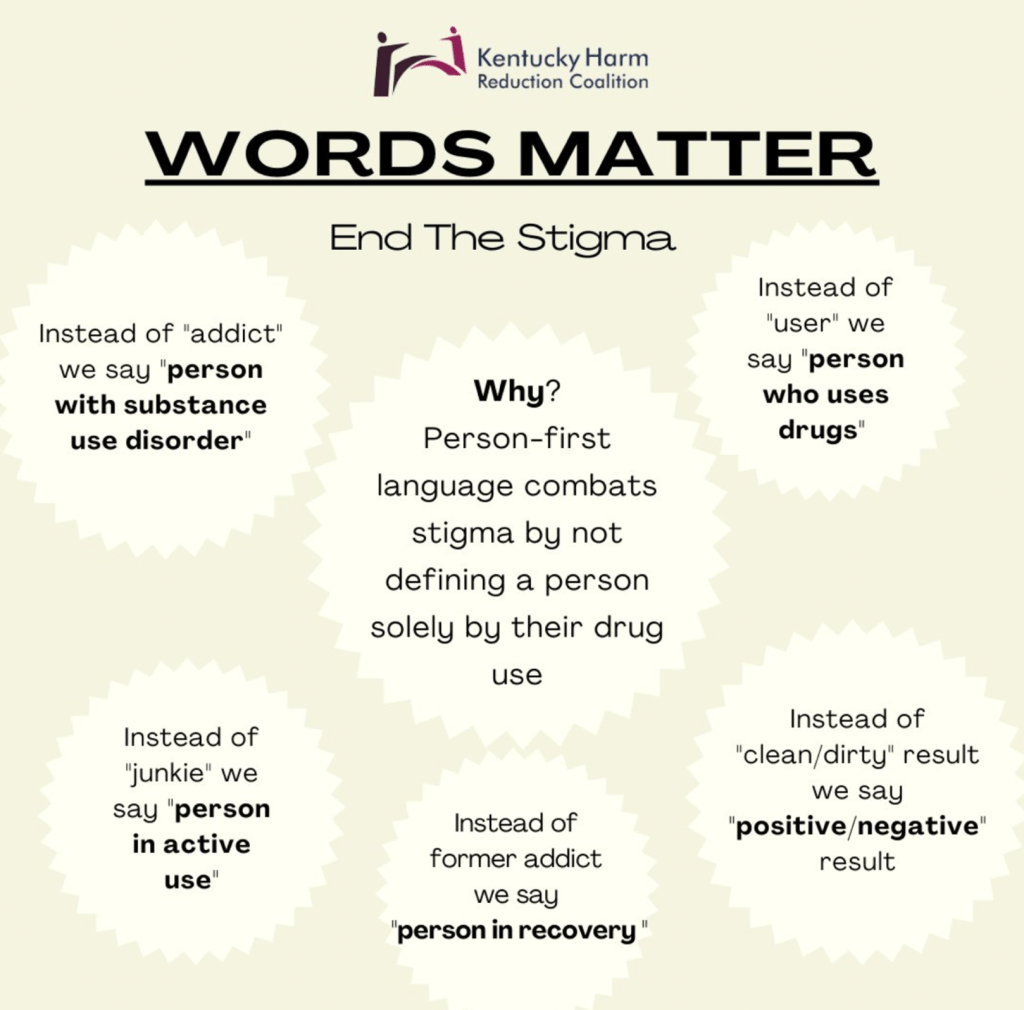

• Despite law enforcement, DEA, policy-makers, and medical experts universally calling for the removal of barriers to accessing buprenorphine, barriers continue to exist, e.g., stigma, costs, irrational fear of diversion, prescriber trepidation, and pharmacist and prescriber fear of regulatory scrutiny. 201 KAR 9:270 contributes to all of these barriers.

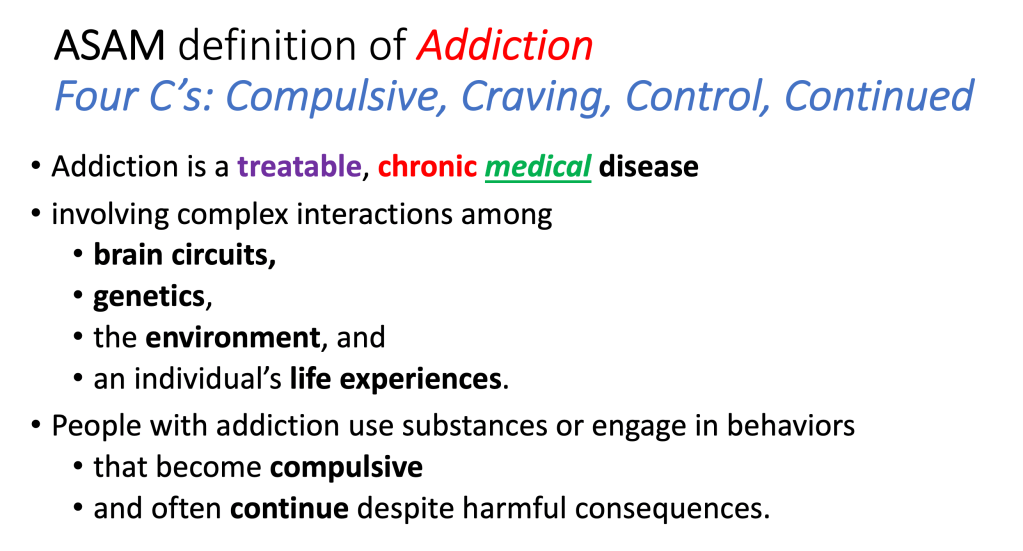

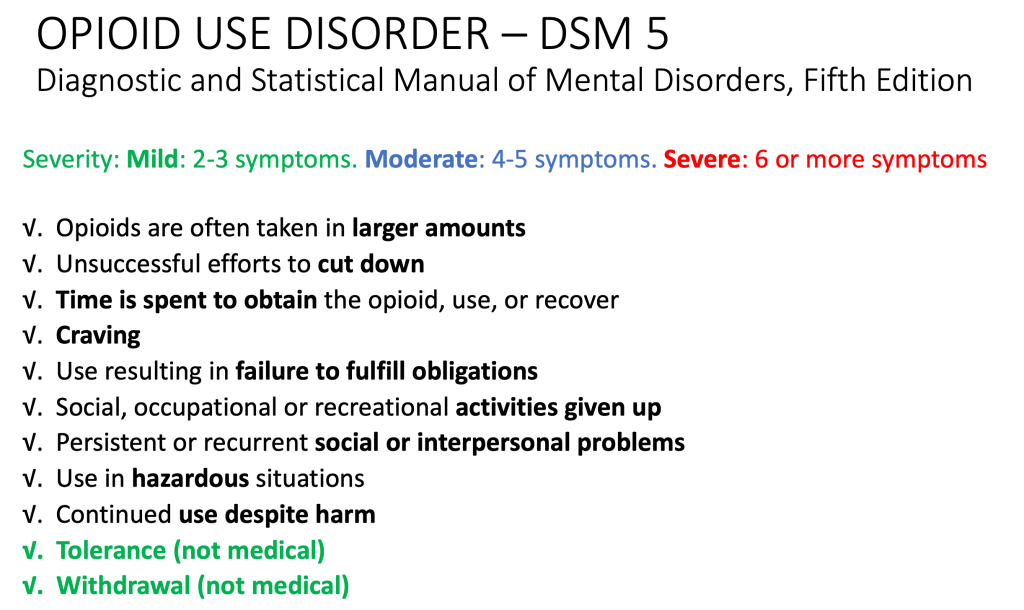

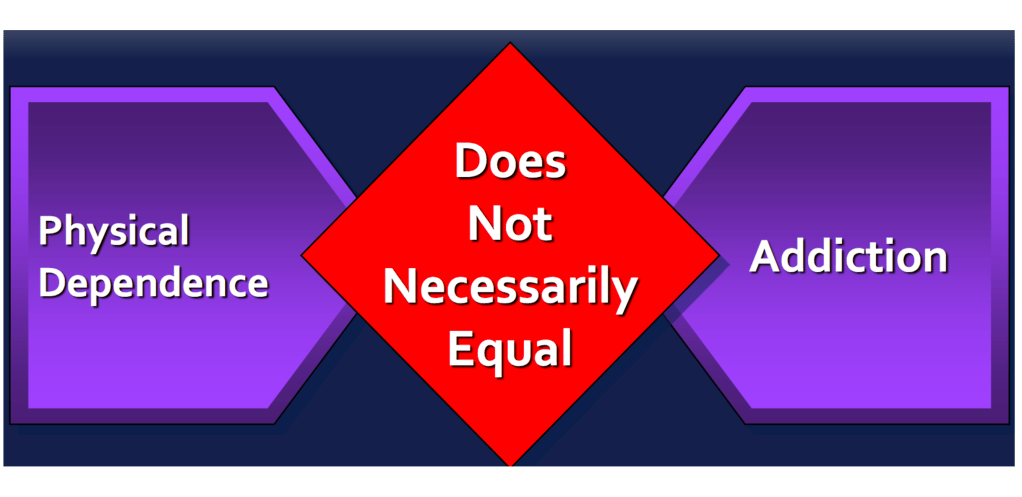

• 201 KAR 9:270 is a barrier to buprenorphine treatment, because it rigidly mandates actions that should be dependent on individual patient circumstances and prescriber clinical judgment; actions such as: frequent in-person evaluations, mandatory specialist consults, numerous urine drug tests, extensive labs, psychological counseling, outdated dosage limits, and irrational limits on medications for co-occurring conditions. Laws mandating such measures are not supported by scientific evidence, federal policies, or clinical practice guidelines from the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

• Frankly, Kentucky’s buprenorphine law 201 KAR 9:270 is years behind the times. To illustrate just how absurd it has become, consider that Kentucky requires a special DEA “X-Waiver” that doesn’t even exist anymore. On December 29, 2022, in an effort to increase access to buprenorphine, Congress eliminated all buprenorphine-specific federal regulations, e.g., the DEA “X-Waiver,” along with caps on the number of patients per prescriber, prescriber limits, mandated education. But 201 KAR 9:270 still requires prescribers to have the “X-Waiver.”

• In sum, Kentucky has perhaps the most outdated, draconian, and harmful buprenorphine regulation in our nation and is one of only 19 states that still have buprenorphine-specific regulations on their books. And sadly, prescriptions for buprenorphine in Kentucky have only decreased at a time when overdose rates are still at record levels. Repealing 201 KAR 9:270 is common sense.

Why is this so?

Because of rapidly evolving scientific and clinical knowledge, it’s impossible for policymakers to create regulations that strictly tell clinicians how to treat addiction with buprenorphine. Beyond that, Kentucky’s deliberate regulatory process is too slow and renders obsolete any attempt at reworking 201 KAR 9:270 even before the ink dries on the page.

Therefore, to save lives, reduce crime, and improve the health and well-being of our communities, please join the Kentucky Society of Addiction Medicine and support repeal of Kentucky’s buprenorphine regulation 201 KAR 9:270. This decade old law is outdated, unfixable, unnecessary, and harms the people it was intended to help. It mandates actions that are not supported by evidence, actions that inhibit access to treatment, actions that lead to increase drug related crime, and actions that promote fraud, waste, and abuse.

Rather than discourage drug diversion, 201 KAR 9:270 actually worsens drug related crime and diversion. And tragically, Kentuckians struggling with addiction are needlessly dying because of barriers to treatment caused by this law.

Repeal of 201 KAR 9:270 would allow buprenorphine to assume its rightful place in the category of DEA Schedule III medications with low risk, allowing clinicians to prescribe buprenorphine for its legitimate medical purpose in the usual course of sound professional practice. Make our communities safer and healthier. Repeal of 201 KAR 9:270 is critically necessary.

A summation of clinical, social, and scientific evidence, as well as expert opinion and federal policy focusing on DIVERSION, CRIME, and ACCESS:

- Buprenorphine DIVERSION is driven by those who lack a prescription, and the risks associated with diversion of buprenorphine are outweighed by the risks of denying patients access to buprenorphine, via Prosecutor’s Office, Washtenaw County, MI. https://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/30331/Law-Enforcement-Leaders-Comment-Re-RIN-1117-AB78

- Failing to access buprenorphine treatment was the strongest predictor of buprenorphine DIVERSION, via University of Kentucky. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3449053/

- Increasing buprenorphine access is an urgent priority to reduce the likelihood of buprenorphine, DIVERSION, overdose and death, via joint UofL and UK study in Appalachia region. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871620300028?via%3Dihub

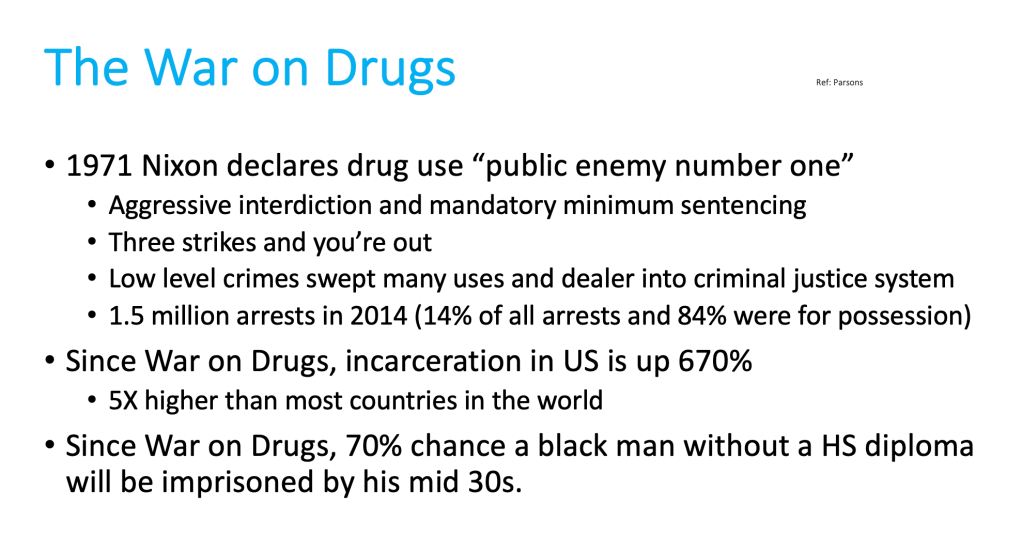

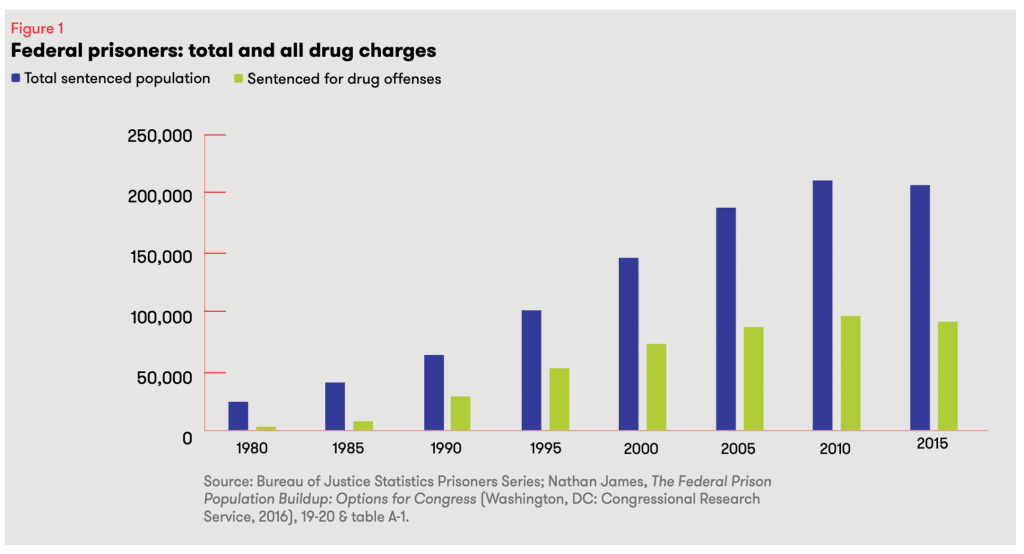

- Treatment with buprenorphine was associated with a REDUCTION IN ARRESTS, via Addiction Medicine, the official journal of ASAM. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30916463/

- Substance use service presence, including buprenorphine treatment, predicts REDUCTIONS in serious violent CRIMES, burglaries, and motor vehicle THEFTS, via University of Pittsburgh. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395924000148?via%3Dihub

- Incarcerated adults with opioid use disorder who received buprenorphine had a REDUCED likelihood of being ARRESTED or returning to jail or prison after release, via University of Massachusetts study. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8852331/pdf/nihms-1768879.pdf

- A misplaced fear of DIVERSION should not limit access to buprenorphine, via U.S. Congressional leadership. https://kuster.house.gov/uploadedfiles/dea_letter_buprenorphine.pdf

- The risk of buprenorphine misuse and DIVERSION is low, via U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports/all/2023/the-risk-of-misuse-and-diversion-of-buprenorphine-for-opioid-use-disorder-in-medicare-part-d-continues-to-appear-low-2022/

- Any steps taken to minimize buprenorphine DIVERSION and misuse must be careful not to undermine the positive patient and public health benefits gained from expanded treatment access, via University of Kentucky. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25221984/

- DIVERSION of buprenorphine is actually associated with a reduction in overdose deaths, via Wayne State University. https://behaviorhealthjustice.wayne.edu/ote/diversion_brief_7_20.pdf

- Increasing access to evidence-based treatment may be the most effective policy solution to reduce DIVERSION, via American Society of Addiction Medicine. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/statement-on-regulation-of-obot.pdf

- Buprenorphine “misuse” is associated with self-treatment of opioid withdrawal and lack of access to treatment, via Center on Alcohol, Substance Use and Addictions. https://hsc.unm.edu/medicine/research/swctn/_pdfs/bupe-fact-sheet.pdf

- There is an “urgent public health need for continued access to buprenorphine as medication for opioid use disorder in the context of the continuing opioid public health crisis,” via DEA 21 CFR Part 1307 (11/19/2024). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/11/19/2024-27018/third-temporary-extension-of-covid-19-telemedicine-flexibilities-for-prescription-of-controlled

- “There are no longer any limits or patient caps on the number of patients a prescriber may treat for opioid use disorder with buprenorphine,” via U.S. D.O.J., Drug Enforcement Administration https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/docs/A-23-0020-Dear-Registrant-Letter-Signed.pdf

- Barriers to treatment with buprenorphine include “Aggressive enforcement strategies by the DEA and several state attorneys general—including increases in raiding, auditing, and launching criminal investigations of waivered providers,” via National Academies of Science. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25310/chapter/7#120

- Policymakers must address regulatory policies that inhibit low barrier buprenorphine treatment, which improves outcomes for individuals, as well as communities, affected by substance use disorders, via Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Low-barrier buprenorphine treatment not only expands access to more patients, but it does so equitably, via Beasley School of Law, Temple University. https://phlr.org/content/legal-barriers-buprenorphine-vital-tool-managing-recovery-and-preventing-opioid-overdose

- Sadly, despite the elimination of all buprenorphine-specific federal regulation and the wealth of quality evidence of the life-saving and crime-reducing benefits of buprenorphine, dispensing of buprenorphine in KY actually decreased by 5.6% from 2022 to 2023, via AMA. https://end-overdose-epidemic.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AMA-2024-Advocacy-Epidemic-report-buprenorphine-IQVIA_FINAL.pdf

- The AMA has called upon states to review their laws and other policies to ensure that they remove barriers to buprenorphine treatment, via AMA Overdose Epidemic Report 2024. https://end-overdose-epidemic.org/highlights/ama-reports/2024-report/

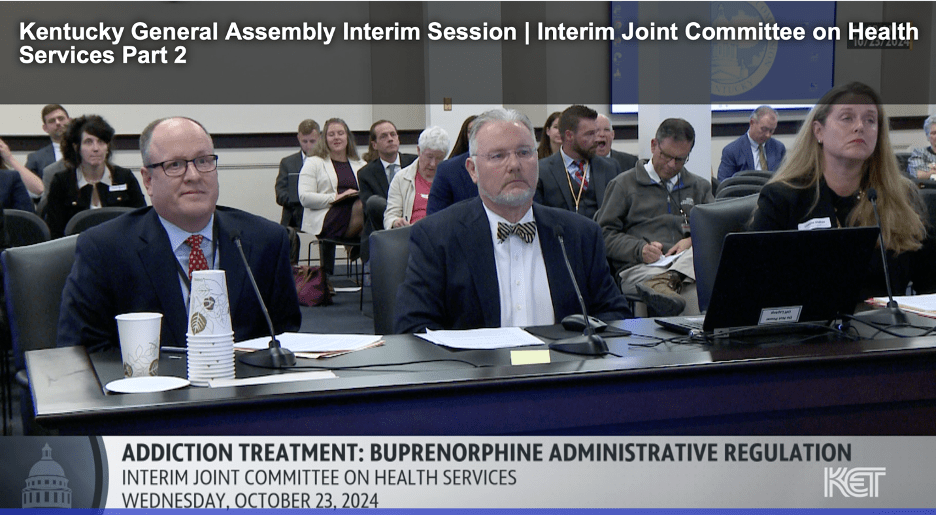

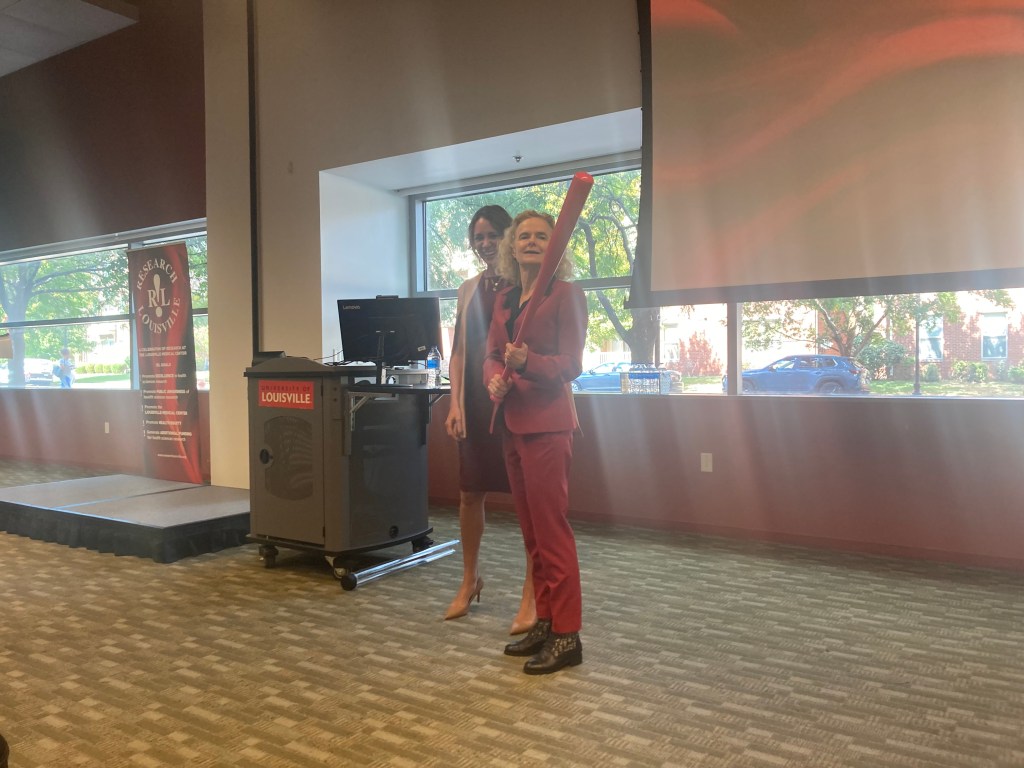

- Because KY’s regulation 201 KAR 9:270 is a recognized barrier to Kentuckians’ access to treatment with buprenorphine, the Kentucky Society of Addiction Medicine is calling for the repeal of this outdated, unnecessary, and harmful regulation, via KYSAM. https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/366/30824/10%2023%202024%204.%20Murphy%20-%20KSAM%20Statement.pdf

Barriers to care caused by 201 KAR 9:270 include:

A bill to increase access to buprenorphine is not a new idea.

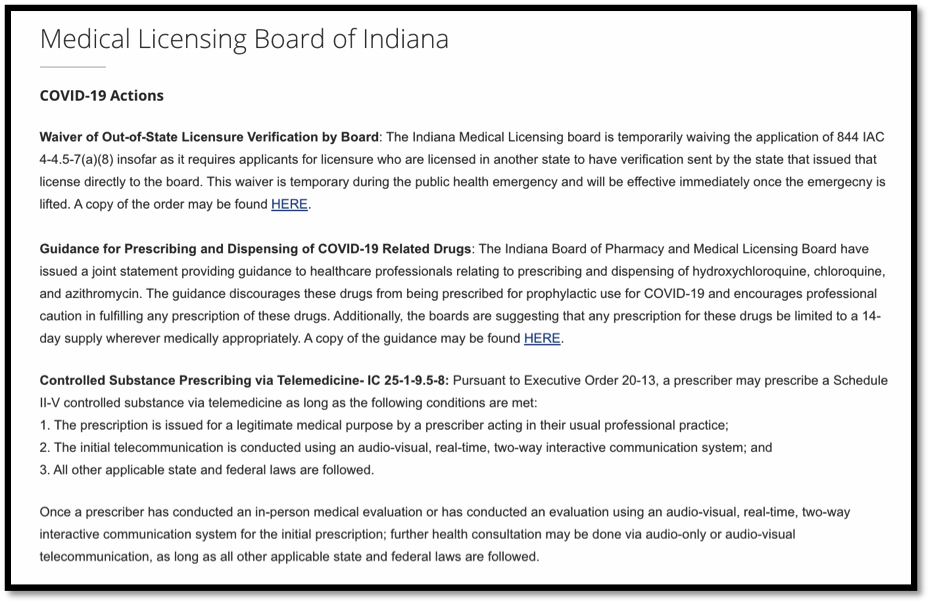

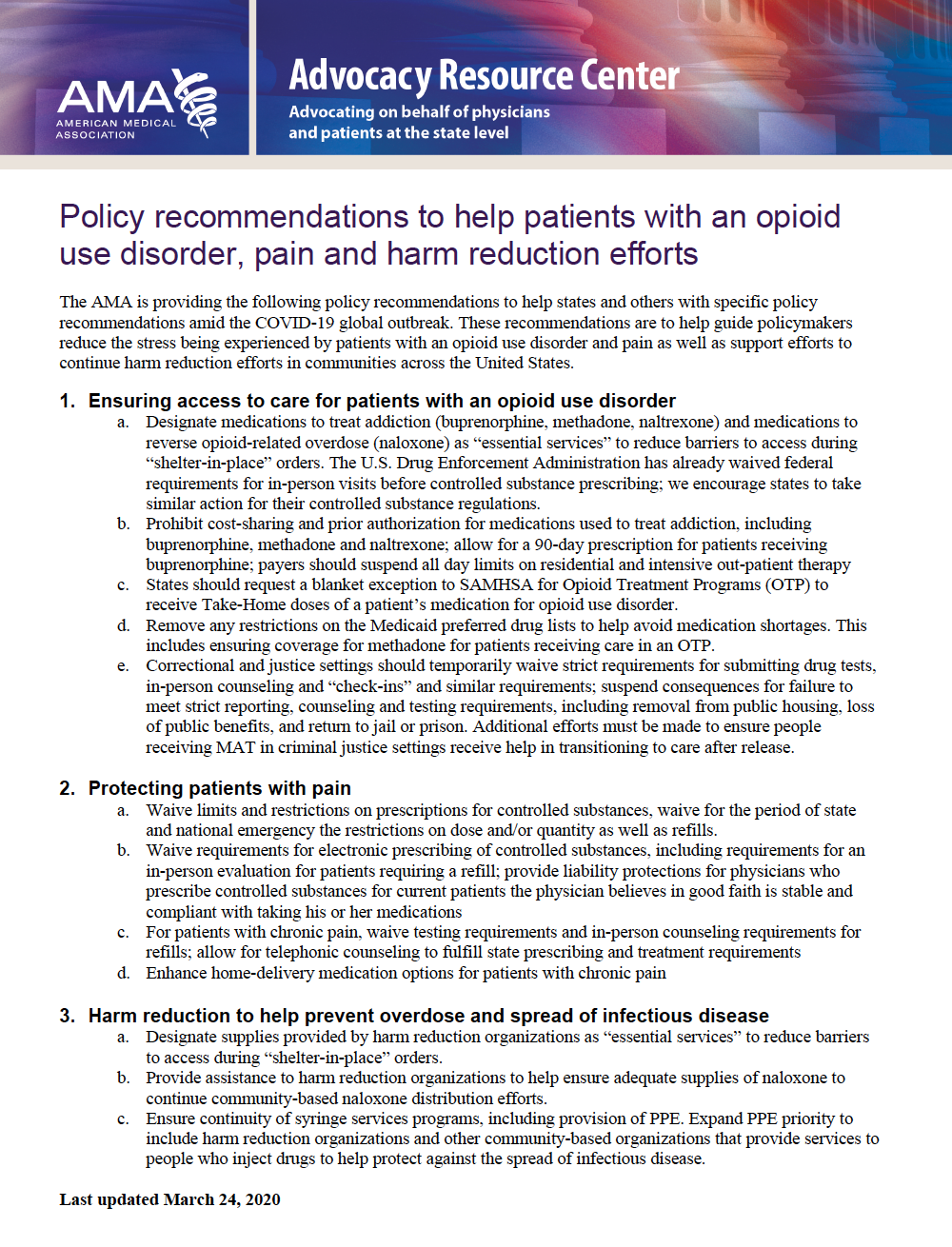

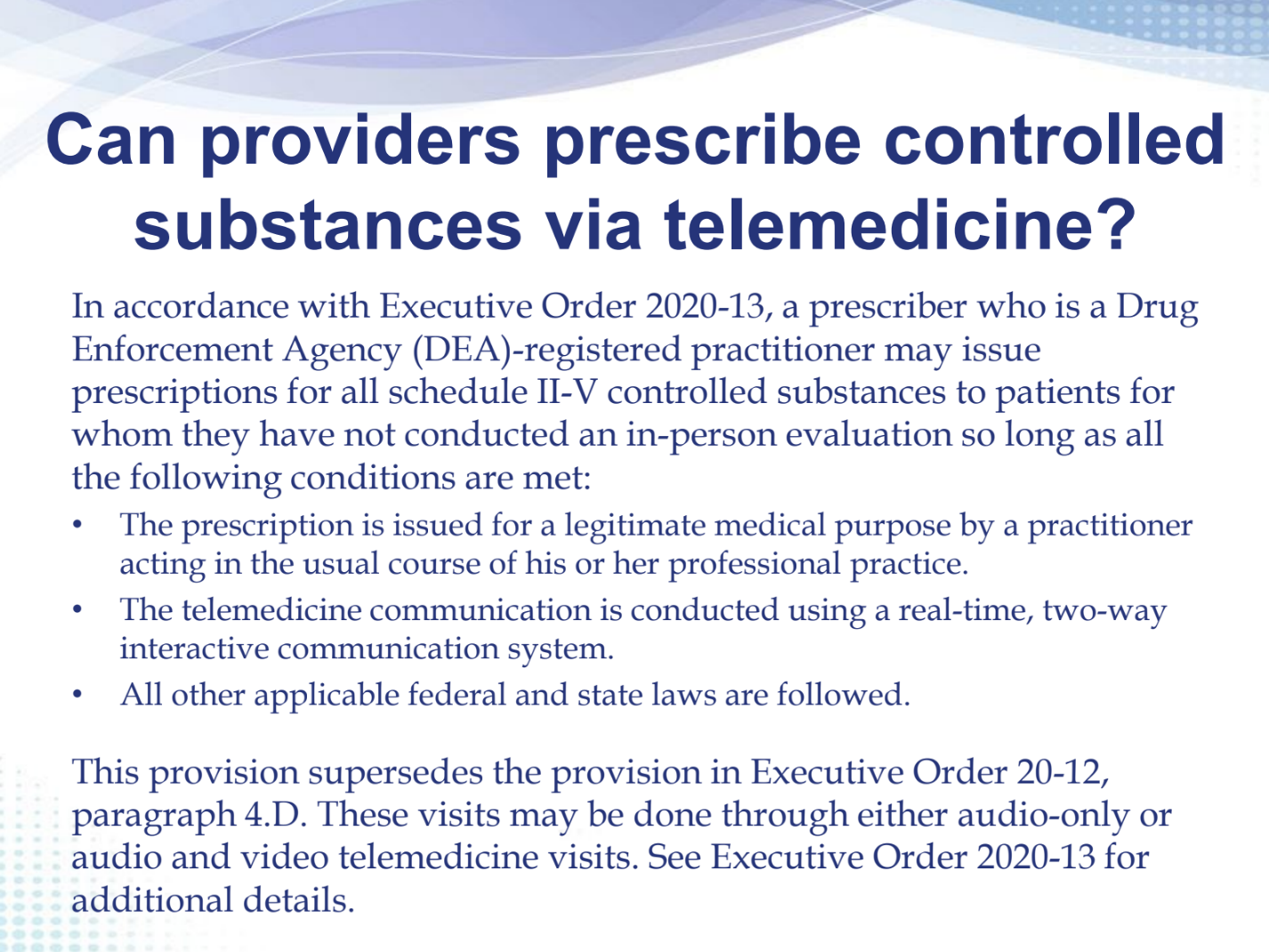

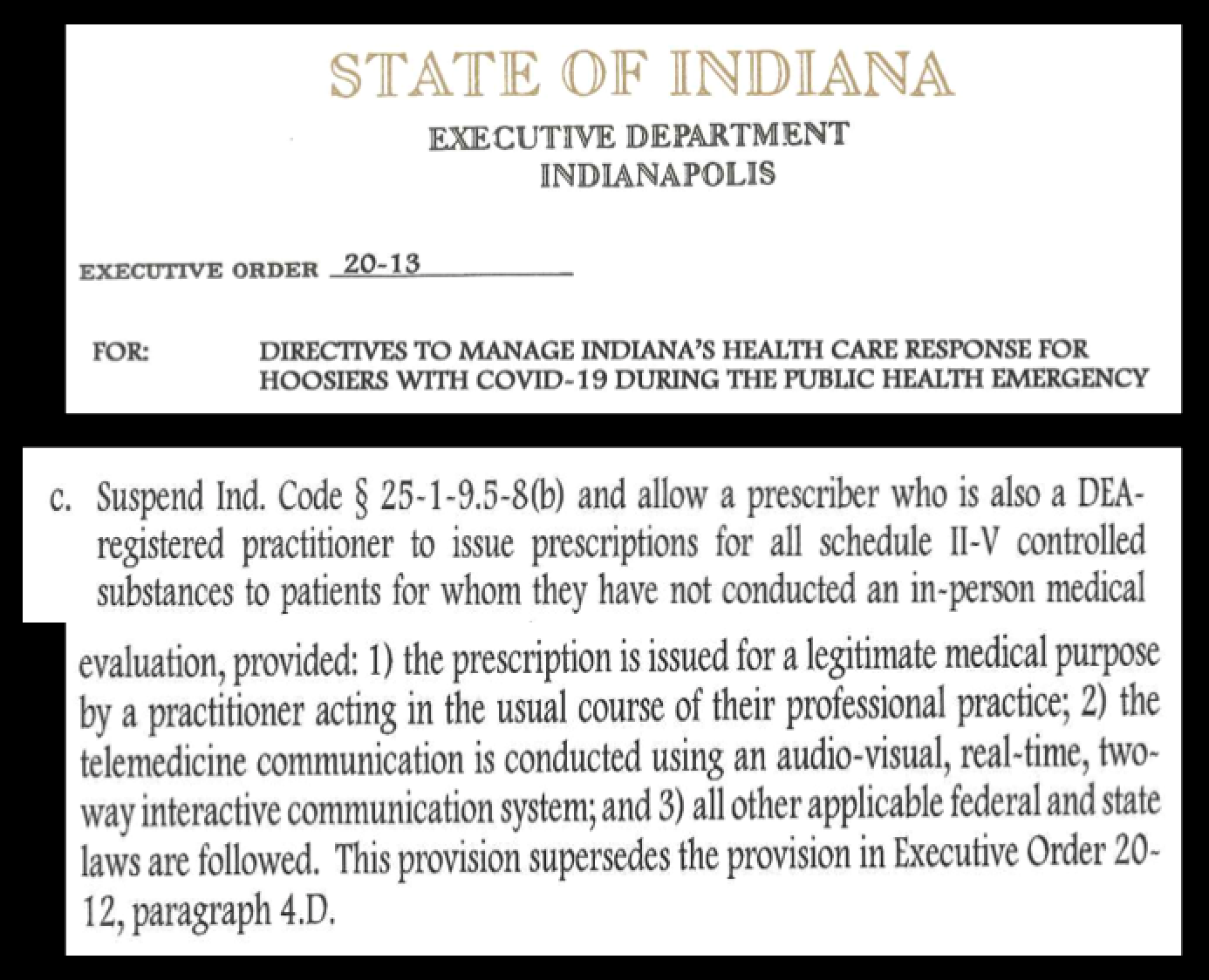

The Kentucky Medical Association (KMA), American Medical Association, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) support a bill (House Bill 121) that would remove insurance barriers to treatment with buprenorphine. The rationale supporting House Bill 121 (noted below) also supports the Kentucky Society of Addiction Medicine’s call for repeal of 201 KAR 9:270. For context, I encourage you to read the following “one-page” support document from the AMA:

For more information, please go to my blog CONFLUENTIAL TRUTH https://jamespmurphymd.com and start scrolling. Related stories begin with my post on June 28, 2024 about a petition to the Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure…