On April 12, 2014 my Norton Healthcare colleagues bestowed upon me the 17th R. Dietz Wolfe Education Award. Hopefully my presentation of the Wolfe Lecture adequately honored the legacy of the esteemed and beloved Dr. Wolfe.

For now, I humbly offer this synopsis…

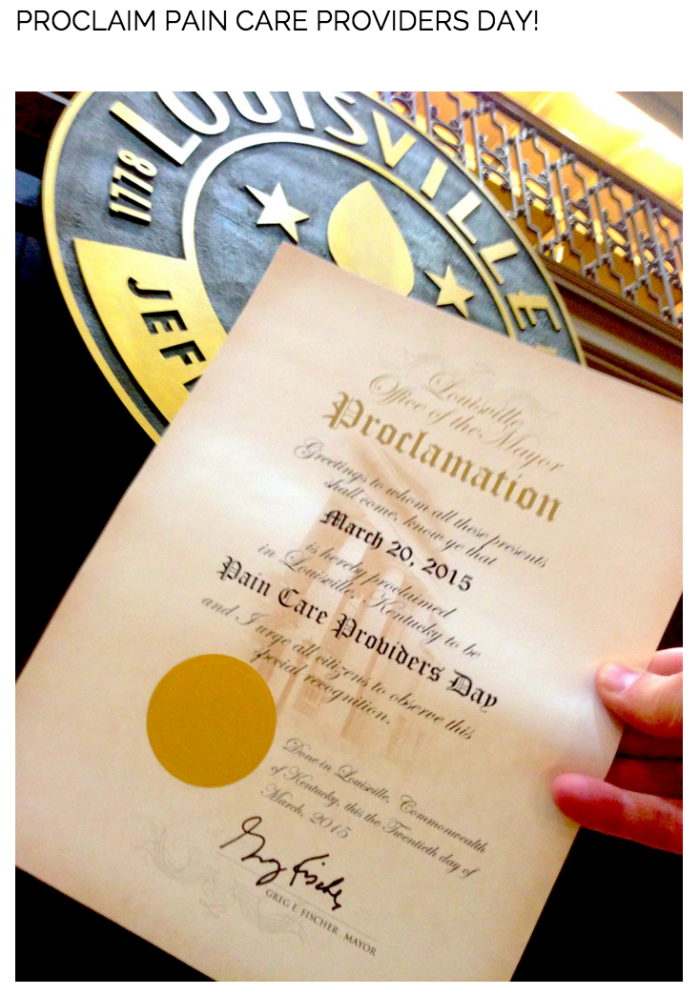

Note: This article was updated on April 1, 2015 to reflect the most recent changes to states’ regulations.

The Dream of Pain Care… Enough to Cope

– the 17th R. Dietz Wolfe Memorial Lecture

the algiatrist

a private place

study her face

fix on his eyes

feel her sinew

give an embrace

innovation

radiation

numb a raw nerve

eradicate

pain creation

to interlope

to offer hope

through some relief

tiny solace

enough to cope

– James Patrick Murphy

Contrary to what one might think, it is generally not difficult to satisfy the needs of patients with chronic pain. Like the poem says, they simply need “enough to cope.” What’s difficult is the juggling act providers must perform to keep three “balls” in the air: patients must do well, regulations must be followed, and drug abuse must be prevented. Drop any of these three balls and you fall as well.

Sometimes the fall is hard. A couple of weeks ago I learned of a pain doctor in northern Kentucky who, on the heels of lawsuits and a medical board investigation, took his own life.

Then there was Dr. Dennis Sandlin, an eastern Kentucky country doctor who was shot and killed in his office by a patient upset because the doctor would not prescribe pain pills to him without first doing a drug screen.

Unfortunately, these scenarios are not our only threat. Federal prosecutors have even tried to use overdose deaths to trigger death penalty statues when seeking indictments against doctors.

And we hear sobering statistics like:

One person dies every 19 minutes from an overdose.

One “addicted” baby is born every hour.

Opioid pain drugs cause more overdose deaths than heroin and cocaine combined.

And now more people die from drug overdose than car accidents.

For this crisis physicians take the brunt of the pundits’ blame, despite the fact that more than two-thirds of the diverted medications are acquired from family, friends, and acquaintances – not from a prescription by their doctor.

So why do it? Why treat chronic pain?

Perhaps because:

Over 100 million Americans suffer from pain, and that number is growing.

Pain affects more Americans than cancer, heart disease, and diabetes combined.

Up to 75% of us endure our dying days in pain.

True. But pain care, perhaps, means a little bit more?

To answer that question we must first understand what pain is: an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.

Second, let’s understand the distinction between addiction and abuse. Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Drug abuse describes behavior born of bad decision-making; not the disease of addiction. But indeed, bad choices, bad behavior, and drug misuse lead to crime, accidents, social instability, and addiction. The developing adolescent brain is particularly susceptible to addiction, while the elderly brain is practically immune.

Third, let’s understand the risk factors for addiction: (a) environmental, (b) patient-related, and (c) drug-related. We cannot control our patient’s environment, occupation, peer group, family history, or psychiatric issues. But we can gather information and get a feel for his or her risk level. Then we can control what we prescribe – understanding the characteristics of an “addictive” drug include the drug’s availability, cost, how fast it gets to the brain (i.e. lipid solubility), and the strength of the “buzz” it produces.

And thus we can understand how important it is to prescribe the lowest dose possible for the minimum amount of time necessary, based on the level of risk in properly screened patients; then reassess. When in doubt, prescribe even less and reassess more often. Never feel obligated to prescribe more than what you are comfortable prescribing. Pain may be the number one reason a patient visits a doctor and pain care is indeed a patient’s right; however, controlled substances for pain care are a privilege. And just like it is with prescribers, the patients have responsibilities and obligations to meet, lest they endanger their privileges. They must become good stewards of the medications they are prescribed.

Despite these serious risks to their community, their patients, and their medical licenses, physicians regularly rise to the occasion and treat pain. Over the past year as President of the Greater Louisville Medical Society, I have written a monthly article for our journal, Louisville Medicine. The reasons that physicians so often rise are woven throughout those essays. Here are few selected passages…

*

June: We have core values that we share, and when our strategy is in line with achieving the greater good our choice of profession becomes a higher calling.

*

July: We can positively affect people’s lives in a dramatic way and on a grand scale if we commit to our shared values, reconnect and work together. It is not only possible. It is our inherent duty.

*

August: Think back to when you were happiest as a physician. It was probably when you did something that was completely selfless, without any concern that the benefit outweighed the cost, without consideration of a return on investment.

*

September: It is why we started down this tortuous path. It’s why we gave up our youth to endless lectures, textbooks, labs, insomnia, and stress, risked our health, and stole from our family life. We went into debt, endured ridicule on morning rounds, and exposed our careers to legal ruin – all so we could commit to helping the people important to our profession: our patients.

*

October: Her strength, courage and positive attitude have always inspired me. In the cacophony of that noisy mall time stood still as our eyes met. I told her who I was and how inspiring she is to me. She smiled and we hugged. That was a moment of confluential truth. Never take for granted this precious gift.

*

November: I can never be 100 percent sure why I do what I do… but I do know the best decision is always the honest decision, regardless.

*

December: I have been blessed with the opportunity to connect intimately with people on many levels. I’ve noticed those who preserve their joy despite insurmountable challenges… They have perspective. Humans are the only organisms aware of concepts like the past, the future, beauty, love, death, and eternity.

*

January: Every imperceptible moment that passes is not only a new reality; it is rebirth, renewal, and redefinition. How will I define myself?

*

February: The place where you started is your true self; the self that is your center; the self that creates your thoughts and actions. Regardless of your life’s circumstances, success is achieved when your thoughts and actions are in harmony with the true you.

*

March: Failure can be painful. It exposes vulnerability. Physicians, myself included, can be very hard on ourselves sometimes, thinking that by intense training and adherence to protocol, preparation, and planning we are somehow immune to failure. This is, of course, not true. Failure is painful – necessary pain – providing motivation to change, evolve, and realize your role in nature’s play of perfection. Failure is not a result as much as it is a feeling. Failure is… a conduit to greatness.

*

April: I will connect with you as a person – not a diagnosis. …No phone calls, no texting, no social media are allowed to come between you and me. Only then, with laser focus, do I proceed. The job demands this. You deserve this.

*

May: There is a shortage in our profession – a shortage of practical dreamers who can remain child, student, explorer, and physician. Your profession and your patients need you to be this physician. And you need you to be this person.

*

While becoming this physician requires the acquisition of vast knowledge, no one cares what you know until they know that you care. But even the most caring physicians find it hard to keep aim at the moving target of pain regulations. Still, if we are going to do this (i.e. treat pain) we should do it right; in a manner that keeps our community safe and our medical licenses secure.

Throughout my years of medical training I have organized data by creating poems, algorithms, and acronyms. It’s been helpful for me. Maybe they will be helpful for you. Here are some such aids I find useful in the care of pain patients.

AAAA – items to address at pain reassessments

Analgesia level (e.g. a “zero to ten” scale)

Activity level (e.g. functional goals)

Adverse effects (e.g. side effects)

Aberrancy (e.g. worrisome behavior, diversion, addiction, depression)

*

PPPP – the differential diagnosis when they ask for more medication

Pathology (e.g. new or worsening disease)

Psychology (e.g. depression, anxiety, addiction)

Pharmacology (e.g. tolerance, altered metabolism, hypersensitivity, neuropathic pain)

Police-related (e.g. unlawful diversion)

*

Kentucky has adopted (and revised) a law and numerous regulations that address the prescription of controlled substances. Here’s some helpful advice pertinent to prescribers in Kentucky:

Plan to THINK – What to do initially when prescribing for the first 90 days

Plan – Document why the plan includes controlled substances.

Teach – Educate the patient about proper use and disposal.

History – Appropriate history and physical

Informed consent – Risks need to be explained and consent documented.

No long acting – Don’t prescribe sustained release opioids for acute pain.

KASPER – Query the state’s prescription monitoring program.

*

COMPLIANCE – That which needs to be done by the 90 day mark

C Compliance monitoring (i.e. Query KASPER, check a urine drug screen)

O Old records (obtain more records if necessary)

M Mental health screening (i.e. depression, anxiety, personality disorders)

P Plan (establish specific functional goals for periodic review)

L Legitimate working diagnosis established (i.e. objective evidence)

I Informed consent (written) & treatment agreement (recommended)

A ADDICTION / Diversion Screening

N Non-controlled medications tried before going to controlled substances.

C Comprehensive history needs to be obtained and documented.

E Exam “appropriate” to establish baselines for follow-up.

*

PQRST – That which needs to be ongoing after the ninety-day mark

P Periodic review (after the first month, up to physician’s judgment)

Q Query KASPER every three months

R Refer to specialists and consultants as necessary

S Screen annually for general health concerns

T Toxicology screens (i.e. urine) and pill counts randomly and at intervals dependent on the patient’s level of risk.

For more detail please review: “THE CHRONIC PAIN PATIENT’S GUIDE TO KENTUCKY’S REGULATIONS” -available at https://jamespmurphymd.com/2015/02/13/pathway-to-partnership

Let’s not forget Indiana. In December 2013 emergency regulations in the Hoosier state were enacted. These were updated and filed as permanent regulations on October 7, 2014. Indiana’s permanent pain regulations apply when any of the following conditions are met:

- DOSE & DURATION >15 MED for >3 months

DAILY MED (“morphine equivalent dose”) greater than FIFTEEN for DURATION of more than three consecutive months

Or…

- QUANTITY & DURATION >60 pills for >3 months

More than SIXTY opioid pills per month for DURATION of more than THREE consecutive months

Or…

- PATCHES > 3 months

Any opioid skin patches (e.g., fentanyl or buprenorphine), regardless of the dose or quantity, for DURATION of more than THREE consecutive months

Or…

- Hydrocodone-Only Extended Release

Any hydrocodone-only extended release medication that is NOT in an “abuse deterrent” form, regardless of the DOSE, QUANTITY or DURATION

Or…

- TRAMADOL (My advice) >150 mgm for >3 months

Actual language in the regulations state: “If the patient’s tramadol dose reaches a morphine equivalent dose of more than sixty (60) milligrams per day for more than three (3) consecutive months.”

This tramadol dose limit seems to be overly generous. My advice: Since 150 mgm of tramadol is equivalent to a FIFTEEN (15) MED, I believe it is more consistent with the other Indiana opioid dosage limits to consider TRAMADOL greater than 150 mgm/day for more than THREE consecutive months as the dosage limit congruent with other opioid dosage limits.

Reference: The online opioid calculator from GlobalRPH http://www.globalrph.com/narcoticonv.htm

For more detail please review: “THE CHRONIC PAIN PATIENT’S GUIDE TO INDIANA’S REGULATONS” -available at https://jamespmurphymd.com/2015/03/29/pathway-to-partnership-part-ii-in

Indiana Physicians have DRIVE

When these thresholds are met, Indiana physicians must DRIVE

- DRAMATIC at the start;

- REVIEW the plan, REVISE the plan & REFER if the morphine equivalent dose is greater than 60 mg/day;

- INSPECT at least annually;

- VISIT face-to-face with the patient at least every 4 months; and

- EXAMINE a drug screen if there is any indication.

Drug screening takes up a significant portion of Indiana’s regulations. The regulations actually list eighteen “factors” to consider. But the bottom line is that a drug screen (with lab confirmation) shall be ordered: “At any time the physician determines that it is medically necessary…(for any) factor the physician believes is relevant to making an informed professional judgment about the medical necessity of a prescription.”

Indiana Physicians are DRAMATIC

At the initial evaluation a Hoosier physician must be DRAMATIC

D Diagnosis (establish a “working diagnosis” of the painful condition)

R Records obtained (a diligent effort made to obtain & review)

A Assessment of pain level

M Mental health (and substance abuse) screening

A Activity (functional) goals need to be established

T Tests should be ordered, if indicated

I Instead of opioids, use non-opioid options first

C Conduct a focused history and physical

Both states emphasize the importance of treatment agreements, informed consent, and patient education. These subjects, along with helpful examples are presented in my article: “Are We In Agreement?” -available for review and download at: https://jamespmurphymd.com/2014/02/19/are-we-in-agreement

*

Regardless of one’s locale, treating pain with controlled substances can be dramatic. I’m reminded of a scene from the movie “The Music Man,” where Professor Harold Hill warned the people of River City:

Either you’re closing your eyes to a situation you do not wish to acknowledge, or you are not aware of the caliber of disaster indicated by the presence of a pool hall in your community.

Well my friends, the same emotional message is often said of physicians who treat pain. This “mass-staria” can be lessened by utilizing REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies). REMS has been promulgated by the FDA with the goal of decreasing the risk associated with some risky drugs – especially the opioids.

The yin and yang of REMS is education and monitoring. The informed consent, patient agreement, and educational points together serve as a foundation for a medical practice’s effective REMS program.

Two prime examples of efforts to educate prescribers are (a) the OPIOID course sponsored by the Greater Louisville Medical Society and (b) the First Do No Harm Providers Guide from Indiana’s Prescription Drug Abuse Taskforce.

When both prescriber and patient understand the risks and watch for the telltale signs, early intervention can keep you out of trouble, despite what the Harold Hills of the world might say.

In my experience, most people will do the right thing if they know what the right thing is. President Ronald Reagan’s Cold War policy with the Soviet Union was to “trust but verify.” When you give someone a reputation to live up to, they are positively motivated to deserve that reputation – and deserve that trust. The various measures prescribers take to verify proper use of pain medications provide boundaries that can guide and comfort all parties involved. Beyond the rules, regulations, and guidelines that make up these boundaries, lies the indisputable truth that physicians have an obligation to treat suffering. It’s our calling.

I’m reminded of these words from our departed colleague, Dr. Patrick Hess:

All physicians are artists,

not always in disguise.

Our way of looking at a patient,

allowing our minds to roam,

all over those perceptions of our previous life,

often forgotten,

to scan these memories,

and pull something from our unconscious mind,

all with the purpose of creating something,

something to help the patient.

This creation is,

itself,

a work of art.

When I decided to include this poem in my lecture presentation, I really had no inkling that Patrick Hess was Dr. Wolfe’s “oldest friend.” Nor was I aware Dr. Wolfe’s first love was journalism, or that he was the “bright” nephew of his beloved uncle, famed novelist Thomas Wolfe. I only knew that there was a message of conviction, hope, and inspiration that needed to be heard. I would like to think that these three kindred spirits were in attendance and that they approved of my message. And I would like to think that you will not merely approve, but will take action so that the dream of pain care, enough to cope, devoid of drug abuse, can be realized.

*

This summary is my own opinion and is not legal advice. Each facility and physician should consult its own legal counsel for advice and guidance.

https://jamespmurphymd.com/2014/03/18/is-there-method-to-this-march-madness

https://jamespmurphymd.com/2014/03/18/is-there-method-to-this-march-madness